بنسعيد العلوي لـ «عكاظ»: ليس كل من كتب الرواية أهلاً لها

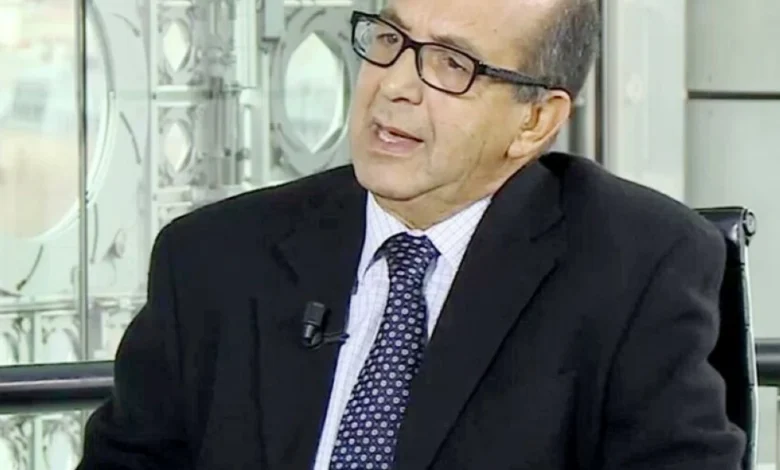

لم يخفت وهج إعجابي وتقديري بالمفكّر الروائي الدكتور سعيد بنسعيد العلوي، منذ لقائي الأول في مهرجان الجنادرية، من نحو عقد ونيّف، إلى اللقاء التالي في ملتقى أصيلة منذ أشهر، فشخصيّة السي سعيد تجمع بين أصالة كَمّ ثقافته، وجمّ أدبه، ورُقي أخلاقه، وعذوبة حديثه، واعتداده بتجربته، كتب في أدبيات الدولة، وناقش الفكر الإصلاحي، وتناول سيرة علّال الفاسي. وخاض غمار الرواية، وصاغ أعذب وأعمق المقالات.. وهنا شواهد على متانة ومكانة شخصية بالغة الثراء المعرفي، فإلى نصّ الحوار..

• كيف كانت مكناس وقت ولادتك؟

•• مدينة لها جناحان، أو إن شئتَ فقل ذات شقين، على غرار كُبريات المدن المغربية؛ جناح (عصري) هو ذاك الذي استحدثه الاستعمار الفرنسي، وكان هذا الجناح أوروبياً في كل شيء، بنيَته، ساكنته، نظام العيش فيه، وشقٌّ أو جناح (تقليدي) هو المدينة الأصيلة، الإسلامية في نظامها وتنظيماتها، وكان الأمر كذلك بموجب الرؤية التي اختطها المُستعمِر الفرنسي، وفي المدينة الأصيلة وُلدتُ، ونشأتُ وتعلّمتُ، وكذا كل الجيل الذي أنتمي إليه.

• من اختار لك اسمك؟

•• اسمي الكامل مركّب، محمد السعيد، محمد اسم جدّي لأمّي، والسعيد جدّي لأبي، ففي اسمي حرص من أبي -رحمه الله- على ترضية الأم والأب معاً. وفي تصرف طائش من الإدارة الفرنسية سيحذف محمد من الاسم وكذا ألف التعريف ولامه (السعيد) ليغدو «سعيد»، دون أن تحذف التسمية عائلياً، وكذا من قبل الأصحاب.

• هل ترى أن للبيئة أثراً على الفرد، من خلال تجربتك الشخصية؟

•• هذا من باب تحصيل الحاصل. وبالنسبة لي كان الأثر قوياً وواضحاً. نشأت في محيط عائلي كان الغالب عليه أن رجاله كانوا من الفقهاء، والوالد كان يمارس مهنة التعليم في المعهد الديني بالمدينة، وكانت له في البيت مكتبة كتب ضخمة، متنوعة إلى حد ما ألفته يستل منها بعد ظهيرة كل يوم كتاباً يغرق في قراءته. كانت المكتبة ضخمة تضم كتباً في التاريخ والأدب وكتباً «عصرية» (في لغة ذلك الزمان) تخرج عن دائرة الفقه والتفسير والحديث. منها على سبيل المثال، كتاب «الهلال»، بعض منشورات «لجنة التأليف والترجمة والنشر»، ومؤلفات في التربية والسير الذاتية. بيد أن تلك المكتبة كانت تبدو لي، في طفولتي عالماً غريباً لم أجرؤ على اقتحامه إلا عند بلوغي المرحلة الثانوية من الدراسة. بيد أن والدي كان يفرح باقتناء ما أطالب به مما كنت أراه في السوق أو أسمع عنه من كتب الأطفال. أشير أيضاً إلى أن صدر الوالد (وهو الفقيه أو «العالم الديني» المهاب الجانب) كان يتسع لأسئلة المراهق الذي كنته، بل ولمشاكسته أيضاً، فيقابلها بابتسامة وسخرية هازلة. ثم إن مكتبة عمومية في (المدينة، كانت غير بعيدة من البيت) أصبحت مكاناً أثيراً إلى نفسي منذ الثانية عشرة من عمري. ثم إنني كنت حريصاً على الذهاب إلى السينما والانغماس في عالمها مرة واحدة في الأسبوع، معتبراً ذلك حقّاً لا يمكن التساهل في إضاعته. وكنت محاطاً بثلة من الأصدقاء، أغلبهم من زملائي في المدرسة، فكنا نلعب سوية أطفالاً (في الحدود الزمنية المسموح فيها بالبقاء خارج البيت)، ثم تعلمنا أن نتسكّع في دروب المدينة العتيقة وأزقتها في حرية منتزعة حين غدونا مراهقين، ثم إننا تعلمنا، سوية، قراءة الروايات وكتب المغامرات؛ وأولها سيرة عنترة وألف ليلة وليلة، نتبادل الكتب والمجلات في متعة وفرح، ولا أريد أن أغفل عن ذكر الراديو وعوالمه الساحرة، نقلب محطات الإذاعة بحثاً عن الأغاني وبرامج التسلية. فهذه صور من البيئة التي نشأت فيها، إذ كان لها أثر قوي على عشقي للخيال وللقراءة وحب الموسيقى، وللأدب أثر قوي في تشكل شخصيتي.

حديث البيئة والتنشئة حديث ذو شجون، فأنا أمسك عن مزيد قول ولو أن في النفس أشواقاً، خشية أن يستغرقنا الحديث فيملأ مجال الحوار برمته.

• متى شعرت بأن مستقبلك مرتهن بالأدب والثقافة؟

•• في زمن المراهقة ومغادرة عالم الطفولة، كنت منبهراً بشخصية (الكاتب)، أشد ما يكون الانبهار، أرسم لها في الخيال صوراً وردية يزيدها التماعاً ما يحيط بأحاديث الأدباء ورواة سيرهم. كنت، على سبيل المثال، منبهراً بيوسف السباعي وبحديثه عن الضباط والجندية وعن صديقه النجم السينمائي أحمد مظهر. وكنت أرى في توفيق الحكيم مثلاً أعلى أحب أن أتشبه به في كل شيء؛ في عشق المسرح، وفي العيش شطراً من العمر، كما عاش في مدينة الفن والسحر والخيال. ثم أجدني، لاحقاً، منجذباً إلى إرنست همنغواي وعوالمه. كنت قارئاً نهماً للرواية، العربية والمترجم منها إلى العربية في مرحلة أولى، فالمكتوب منها باللغة الفرنسية أو المنقول إليها، في مرحلة ثانية. منذ الخامسة عشرة من عمري كنت أحلم أن أصبح (كاتباً) بدوري ولا أرضى بهذه الصفة بديلاً. (وكنت، في سر لا أطلع عليه إلا اثنين من أصدقائي) أكتب قصصاً قصيرة، ومسرحيات وما أزال حتى اليوم أحتفظ برواية، في الوقت الذي كان الأقران يكتبون خواطر ومذكرات وينظمون شعراً غير أنهم «نسوا» ذلك كله فانصرفوا عنه مع التقدم في مراحل الدراسة، إلا عبد ربه فقد ظل حلمه بأن يصبح (روائياً) ملازماً له، وظل دوماً قارئاً نهماً للرواية، وظل (الروائي) يسكن في جوفه حتى شاء الله، في مرحلة جد متقدمة من العمر أن يخرج الروائي من قبوه فيكتب وينشر روايته الأولى.

• بين عنايتك بالفكر الفلسفة وانشغالك بالإنتاج الروائي، من أنت في نظر نفسك؟

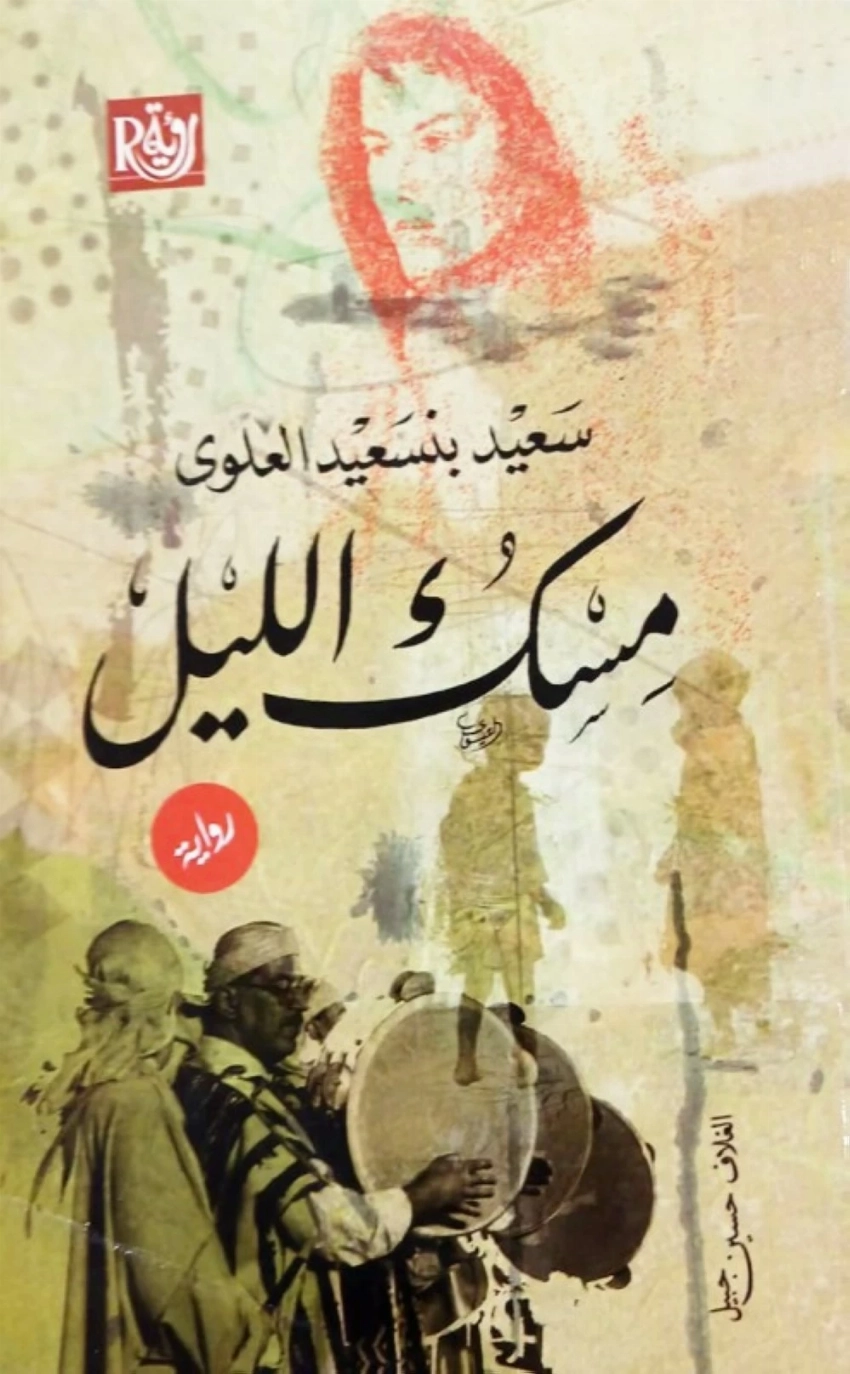

•• سؤال لعل الأجدر بي أن أطرحه على قارئي. حين نشرت روايتي الأولى (مسك الليل) -وصادفت بحمد الله استحساناً وترحيباً من ثلة من النقاد وأساتذة الأدب في الجامعة المغربية- أعتبر الأمر، في نظر غالبية الزملاء في الجامعة وكذا الصحفيين ونقاد الأدب، أن الأمر يتعلق في المغرب بـ(ظاهرة) جديدة: ظاهرة الروائيين الذين يفدون إلى الرواية من عوالم التاريخ والفلسفة والسياسة، فأنا أحد هؤلاء الوافدين. ثم إنني أخذت، بالتدريج، أفقد صفة (الوافد) فأصبح اسم العبد الضعيف يذكر، في جملة الذين يذكرون من الروائيين المغاربة، وأعترف أنه أمر يسعدني، بالقدر الذي يحرجني، فهو يخجلني؛ لأنني، في ذهني، أجعل للرواية مكاناً عالياً جداً من الإنتاج الفكري، ليس كل من ينعت بالروائي أهلاً لها -فلا تزال خشية أن أكون في عداد هؤلاء-. أكتفي بالقول إن خمساً من الروايات الست التي أصدرت، شكلت مواد لمذكرات ورسائل جامعية وفصولاً من كتب في النقد لأساتذة جامعيين.

• كم عدد إصداراتك إلى اليوم؟

•• ست روايات، وخمسة عشر كتاباً نظرياً؛ أحدها باللغة الفرنسية، وثلاثة مؤلفات جامعية، مساهمتان اثنتان منها باللغة الفرنسية أيضاً. وصدر أغلب ما نشرته في دور نشر لبنانية وأخرى مصرية، وصدر القليل منها في المغرب ضمن منشورات كلية الآداب في الرباط.

• من الذي ترى أنه «أبو الفلسفة» في المغرب؟

•• لا جدال أنه المرحوم محمد عزيز الحبابي. فهو صاحب أول أطروحة لنيل شهادة الدكتورة (جامعة السوربون سنة 1954)، وهو أول الفلاسفة المغاربة الذين يرتبط اسمه بابتداع مذهب فلسفي (الشخصانية الإسلامية). ثم إن اسم عزيز الحبابي يرتبط في أذهاننا بتأسيس الجامعة العصرية الأولى في المغرب وبدرس الفلسفة فيها: جامعة محمد الخامس.

• كيف يمكن أن تنعكس ثقافة النخبة على سلوك المجتمعات؟

•• لعل القصد بالنخبة في سؤالك، فيما أقدر، هي النخبة الثقافية أو محيط الفئة من الناس التي تنعت بالمثقفين. فإذا كان كذلك فإنّ الجواب عندي يتعلق، من جهة أولى، بالصورة التي ترتسم للمثقف في الوعي الاجتماعي العربي وبالدور الذي نرى أنه له. ويتعلق، من جهة ثانية بارتفاع النسب المئوية لتداول الكتب والمجلات والإقبال على البرامج الثقافية التليفزيونية، وكذا المواقع الثقافية في الشبكة العنكبوتية. ومتى قارنا هذه النسب، في عالمنا العربي، بمثيلاتها في دول أوروبا وأمريكا (شمالها وجنوبها)، وكذا بالدول العظمي في جنوب شرق آسيا فإنّ الأمر يبعث على الآسف والإشفاق من واقعنا العربي. نخبنا المثقفة أبعد ما تكون قدرة على التأثير في مجتمعاتنا العربية. وإذا كان الدور الأساسي للمثقف هو صناعة الوعي والدفع إلى الأمام فإن نخبنا العربية المثقفة في واقعنا الحالي لا تملك من الأمر شيئاً.

• ما موقفك من الجوائز؟ وهل ترى أنها خالية من «الانحياز»؟

•• أود، بمناسبة هذا اللقاء أن أحيي، بصدق وقوة، كل الجهات التي تنظم جوائز للكتاب في عالمنا العربي: جهات رسمية حكومية ومبادرات تنبع من المجتمع المدني. ثم أضيف، عقب التحية والتنويه، أن الأمر ربما لا يخلو، في بعض الأحوال، من سوء تصرف يشوب تنظيم الجائزة (بدءاً من تكوين لجان القراءة والاختيار، وانتهاءً بالبث النهائي الذي يرجع لأسباب متعددة (أجدني في غنى عن ذكرها). وعلى كلٍّ فإن الجهات التي تتولى التخطيط والتدبير (سواء كانت جهات حكومية أو ترجع إلى المجتمع المدني) مطالبة -فيما يبدو لي- بالقيام بمراجعات شاملة قصد القضاء على تفشي ظاهرة «الشللية» (كما يقول الإخوة المصريون)، وباقي الظواهر الأخرى التي تسيء إلى سمعة الجائزة وتشوه صورة الجهة التي تنتمي اليها، ناهيك عن الانعكاسات السلبية على العمل الثقافي وعلى الكتاب العربي.

• متى بدأت علاقتك بالثقافة السعودية؟ ومن أول من لفت انتباهك إليها؟

•• إذا كنت تقصد بالثقافة السعودية الثقافة من حيث هي تعبير ثقافي يتصل بالمجتمع والإنسان السعوديين تحديداً، فإن الجواب المباشر أن هذا الاتصال ابتدأ بالتليفزيون، وما جعلني ألج من عالم السعودية (خارجاً عن صورة السعودية موطن مكة والمدينة وبلد الحج والعمرة)، ثم بدأت تجتمع لدي مشاهدات واتصالات مباشرة مكنني منها حضوري مرات عدة فعاليات مهرجان الجنادرية. وأما إذا كنت تقصد بالسؤال الفكر والثقافة في معنى (الثقافة العالمة) -كما يتحدث عنها علماء الاجتماع- فإن علاقتي بهذه الثقافة علاقة قديمة بتوسط المثقفين السعوديين الذين عرفتهم في العديد من الملتقيات الفكرية، في العالم العربي وخارجه. وكذا الذين عرفتهم من خلال مؤلفاتهم (في الرواية، والفكر السياسي، والدراسات النقدية، وفي صفحات الرأي في الجرائد العربية ذات التوزيع الواسع). وإنني أعتز باكتساب صداقة كوكبة عظيمة من الأصدقاء ترد على الخاطر عفواً أسماء أذكر منها عثمان الرواف، معجب الزهراني، عبدالله الغذامي، أبوبكر باقدر، تركي الحمد، مشاري الذايدي، تركي الدخيل. وأذكر من الذين أسعدني الحظ بمعرفتهم الشاعر السفير والوزير عبدالعزيز خوجة، والوزير أخي إياد مدني، والفاضل النبيل عبدالعزيز السبيل، وأرجو أن تصلهم من خلال هذا المنبر الكريم تحياتي وصادق مودتي، وأستدرك فأقول إن من ذكرت لا يشكلون بالنسبة لي لائحة مقفلة، فإخوتي في المملكة كثر، ومنهم من صار إلى عفو الله، فأنا أترحم عليه.

My admiration and appreciation for the thinker and novelist Dr. Said Bensaid Alawi has not diminished since our first meeting at the Janadriyah Festival nearly a decade ago, to our next encounter at the Asilah Forum a few months ago. Mr. Said’s personality combines the authenticity of his vast culture, the richness of his literature, the nobility of his morals, the sweetness of his speech, and his pride in his experience. He has written on state literature, discussed reformist thought, and addressed the biography of Allal Al-Fassi. He has delved into the realm of novels and crafted the most exquisite and profound articles. Here are testimonies to the strength and significance of a personality rich in knowledge, so here is the text of the dialogue..

• What was Meknes like at the time of your birth?

•• It is a city with two wings, or if you prefer, two aspects, similar to the major Moroccan cities; one (modern) wing is that which was established by French colonialism, and this wing was European in every way—its structure, its inhabitants, its way of life. The other wing, or aspect, is the (traditional) city, authentic and Islamic in its systems and organization. This was also the case according to the vision outlined by the French colonizer. In the authentic city, I was born, raised, and educated, as was the entire generation to which I belong.

• Who chose your name?

•• My full name is compound: Mohammed Al-Said. Mohammed is my maternal grandfather’s name, and Al-Said is my paternal grandfather’s name. In my name, there is a care from my father—may he rest in peace—to please both my mother and father. Due to a reckless act by the French administration, Mohammed was removed from the name, as well as the definite article and the “Al” of “Al-Said,” making it simply “Said,” without the family name being omitted, nor from friends.

• Do you believe that the environment has an effect on the individual, based on your personal experience?

•• This is a matter of obviousness. For me, the effect was strong and clear. I grew up in a family environment where the men were predominantly scholars, and my father practiced the profession of teaching at the religious institute in the city. He had a large library at home, diverse to the extent that he would take a book from it every afternoon to immerse himself in reading. The library was vast, containing books on history and literature, as well as “modern” books (in the language of that time) that fell outside the realm of jurisprudence, interpretation, and hadith. For example, there was the book “Al-Hilal,” some publications from the “Committee for Authorship, Translation, and Publication,” and works on education and biographies. However, that library seemed to me, in my childhood, a strange world I did not dare to invade until I reached high school. My father was pleased to acquire what I requested from the books I saw in the market or heard about for children. I should also mention that my father’s chest (as a revered scholar) was wide enough for the questions of the teenager I was, even for my teasing, which he met with a smile and playful sarcasm. Moreover, a public library in the city (not far from home) became a cherished place for me since I was twelve years old. I was also keen to go to the cinema and immerse myself in its world once a week, considering it a right that should not be neglected. I was surrounded by a group of friends, most of whom were my classmates, and we played together as children (within the permissible time limits for staying outside the house). Then we learned to wander the streets and alleys of the old city freely when we became teenagers, and together we learned to read novels and adventure books; the first of which were the stories of Antara and One Thousand and One Nights. We exchanged books and magazines with joy and pleasure, and I do not want to overlook mentioning the radio and its enchanting worlds, as we flipped through radio stations searching for songs and entertainment programs. These are images from the environment I grew up in, which had a strong effect on my love for imagination, reading, and music, and literature had a profound impact on shaping my personality.

Talking about the environment and upbringing is a topic full of emotions, and I refrain from saying more, even though there are longings in my heart, for fear that the conversation may consume us and fill the entire dialogue space.

• When did you feel that your future was tied to literature and culture?

•• In my adolescence, as I left the world of childhood, I was deeply fascinated by the figure of the (writer), the most intense admiration, envisioning rosy images of them, enhanced by the stories surrounding the lives of writers and narrators. For example, I was captivated by Youssef El Sebai and his discussions about officers and military life and his friend, the movie star Ahmed Mazhar. I saw in Tawfiq Al-Hakim an ideal I wished to emulate in everything; in my love for theater, and in living part of my life as he did in the city of art, magic, and imagination. Later, I found myself drawn to Ernest Hemingway and his worlds. I was an avid reader of novels, both Arabic and those translated into Arabic initially, and those written in French or translated into it in a second phase. Since I was fifteen, I dreamed of becoming a (writer) myself and would not accept any substitute for that title. (And I secretly wrote short stories and plays, which I still keep today, while my peers wrote thoughts and diaries and composed poetry, but they “forgot” all that and turned away from it as they progressed in their studies, except for Abed Rabbo, who always held onto his dream of becoming a (novelist) and remained an avid reader of novels, and the (novelist) resided within him until God willed, at a very advanced stage of life, for the novelist to emerge from his depths to write and publish his first novel.

• Between your interest in philosophical thought and your engagement in novel writing, who are you in your own view?

•• This is a question that perhaps I should pose to my readers. When I published my first novel (Musk of the Night)—which, thank God, received appreciation and welcome from a group of critics and professors of literature at Moroccan universities—I consider this matter, in the view of the majority of my colleagues at the university and also journalists and literary critics, to be a (new phenomenon) in Morocco: the phenomenon of novelists who come to the novel from the worlds of history, philosophy, and politics; I am one of these newcomers. Gradually, I began to lose the label of (newcomer) so that the name of this weak servant is mentioned among those who are recognized as Moroccan novelists, and I admit that this pleases me as much as it embarrasses me; it shames me because, in my mind, I place the novel in a very high position among intellectual production, and not everyone who is labeled as a novelist is worthy of it—so I still fear being among those. I suffice to say that five of the six novels I have published have formed materials for theses, university papers, and chapters in books on criticism by university professors.

• How many publications do you have to date?

•• Six novels and fifteen theoretical books; one of which is in French, and three university publications, two of which are also in French. Most of what I have published has been through Lebanese and Egyptian publishing houses, with a small amount published in Morocco under the Publications of the Faculty of Arts in Rabat.

• Who do you see as the “father of philosophy” in Morocco?

•• There is no doubt that it is the late Mohamed Aziz Al-Hbabbi. He is the author of the first thesis for a doctorate (Sorbonne University in 1954), and he is one of the first Moroccan philosophers whose name is associated with the invention of a philosophical doctrine (Islamic personalism). Moreover, the name Aziz Al-Hbabbi is linked in our minds to the establishment of the first modern university in Morocco and to the teaching of philosophy there: Mohammed V University.

• How can the culture of the elite reflect on the behavior of societies?

•• Perhaps the elite you refer to in your question, as I understand it, is the cultural elite or the circle of people who are labeled as intellectuals. If that is the case, then my answer relates, on the one hand, to the image that is formed of the intellectual in Arab social consciousness and to the role we see that he has. On the other hand, it relates to the rising percentages of book and magazine circulation and the demand for cultural television programs, as well as cultural websites on the internet. When we compare these percentages in our Arab world with their counterparts in Europe and America (both North and South), as well as in the major countries of Southeast Asia, the situation is indeed disheartening and evokes pity for our Arab reality. Our intellectual elite are far from being able to influence our Arab societies. If the primary role of the intellectual is to create awareness and push forward, then our current Arab intellectual elite possess nothing in this regard.

• What is your stance on awards? Do you see them as free from “bias”?

•• On the occasion of this meeting, I would like to sincerely and strongly salute all the entities that organize awards for writers in our Arab world: official governmental bodies and initiatives arising from civil society. I would also add, after this greeting and commendation, that the matter may not be devoid, in some cases, of mismanagement that taints the organization of the award (starting from the formation of reading and selection committees, to the final decision which may be influenced by various reasons (which I find unnecessary to mention). In any case, the entities responsible for planning and managing (whether governmental or belonging to civil society) are required—seemingly—to conduct comprehensive reviews to eliminate the spread of the phenomenon of “cliques” (as our Egyptian brothers say), along with other phenomena that tarnish the reputation of the award and distort the image of the entity to which it belongs, not to mention the negative repercussions on cultural work and on Arab writers.

• When did your relationship with Saudi culture begin? Who first drew your attention to it?

•• If by Saudi culture you mean culture as a cultural expression specifically related to Saudi society and people, then the direct answer is that this connection began with television, which allowed me to enter the world of Saudi Arabia (beyond the image of Saudi Arabia as the home of Mecca and Medina and the land of pilgrimage and Umrah). Then I began to gather observations and direct contacts made possible by my attendance at several events of the Janadriyah Festival. If you mean by the question thought and culture in the sense of (high culture)—as discussed by sociologists—then my relationship with this culture is an old one, facilitated by the Saudi intellectuals I met at various intellectual gatherings, both in the Arab world and abroad. I also got to know them through their works (in novels, political thought, critical studies, and in the opinion pages of widely circulated Arab newspapers). I take pride in having gained the friendship of a great group of friends, among whom I casually recall names such as Othman Al-Rawaf, Mujahed Al-Zahrani, Abdullah Al-Ghudhami, Abu Bakr Baqdar, Turki Al-Hamd, Mishari Al-Dhiyadi, and Turki Al-Dakhil. I also mention those I was fortunate to meet, such as the poet, ambassador, and minister Abdulaziz Khoja, Minister and my brother Iyad Madani, and the noble Abdulaziz Al-Sabeel. I hope they receive my greetings and sincere affection through this esteemed platform. I must add that those I mentioned do not form a closed list for me; my brothers in the Kingdom are many, and some have returned to God’s mercy, and I pray for them.